Rebecca-Eli M. Long, M.A.

(they/them/theirs)

Scholar-activist of Disability Worlds

Ethnographic Knitter

Ph.D. Candidate at Purdue University

About

I'm a scholar, activist, and artist committed to disability communities and disrupting ableism across geographic and disciplinary contexts. Raised in Warren County, North Carolina, I care about justice, wellbeing, and the environment, especially in rural, out of the way places.I moved to western North Carolina for college, and I completed both my Bachelors and Masters degrees at Appalachian State University. With B.A.'s in Anthropology and Art, an M.A. in Appalachian Studies, and a graduate certificate in Gerontology, I learned how to work within a range of academic disciplinary frameworks, as well as alongside community partners. While working on my M.A., I also participated in community based research projects around streambank restoration with the New River Conservancy as part of the Appalachian Teaching Project. Though I no longer live in Appalachia, I remain connected to the region through ongoing research projects.In 2020, I began a dual-Ph.D. program in Anthropology and Gerontology at Purdue University, motivated by the lack of research on aging and autism. I approach this area of inquiry through disability and life course anthropologies, in order to better understand how autistic people create lives in a world marked by pervasive ableism. I believe that it's crucial to understand how structural violence impacts life chances, as well as find moments of joy even in the midst of violence.

Research

As a scholar, activist, and artist, I creatively tell stories of lived experiences to advance social change. I focus on disability, social movements, and the various creative ways that disabled people shape our worlds. I am particularly interested in how creative and arts-based research methods can challenge compulsory ablebodied/ablemindedness and show different possibilities for the future.My dissertation research challenges the idea that a good future is one without autism–and therefore without autistic people. Many conversations around autism in the United States focus on the early identification, intervention, and prevention of autistic children. My work instead focuses on how autistic adults’ interests and passions show us that autistic lives and futures are possible, even desirable. Combining disability, life course, and multimodal anthropologies, I use knitting to materialize ethnographic narratives of autistic joy.As a transdisciplinary (and sometimes un-disciplined) scholar, my work traces ableism across varied terrains. I have maintained a program of research around disability in Appalachia. I argue that disability provides a lens to understand how Appalachia has been constructed as backward and deviant. Even though the terms "disability rights" and "disability justice" aren't used much in Appalachia, these struggles take place within movements for labor, health equity, and queerness. By focusing on the role that disability played in these broader movements, I hope to show the value of an analysis rooted in critical disability studies and contribute to understanding disability in rural areas.For more information about my research and other professional experiences, see my CV.

Knitting

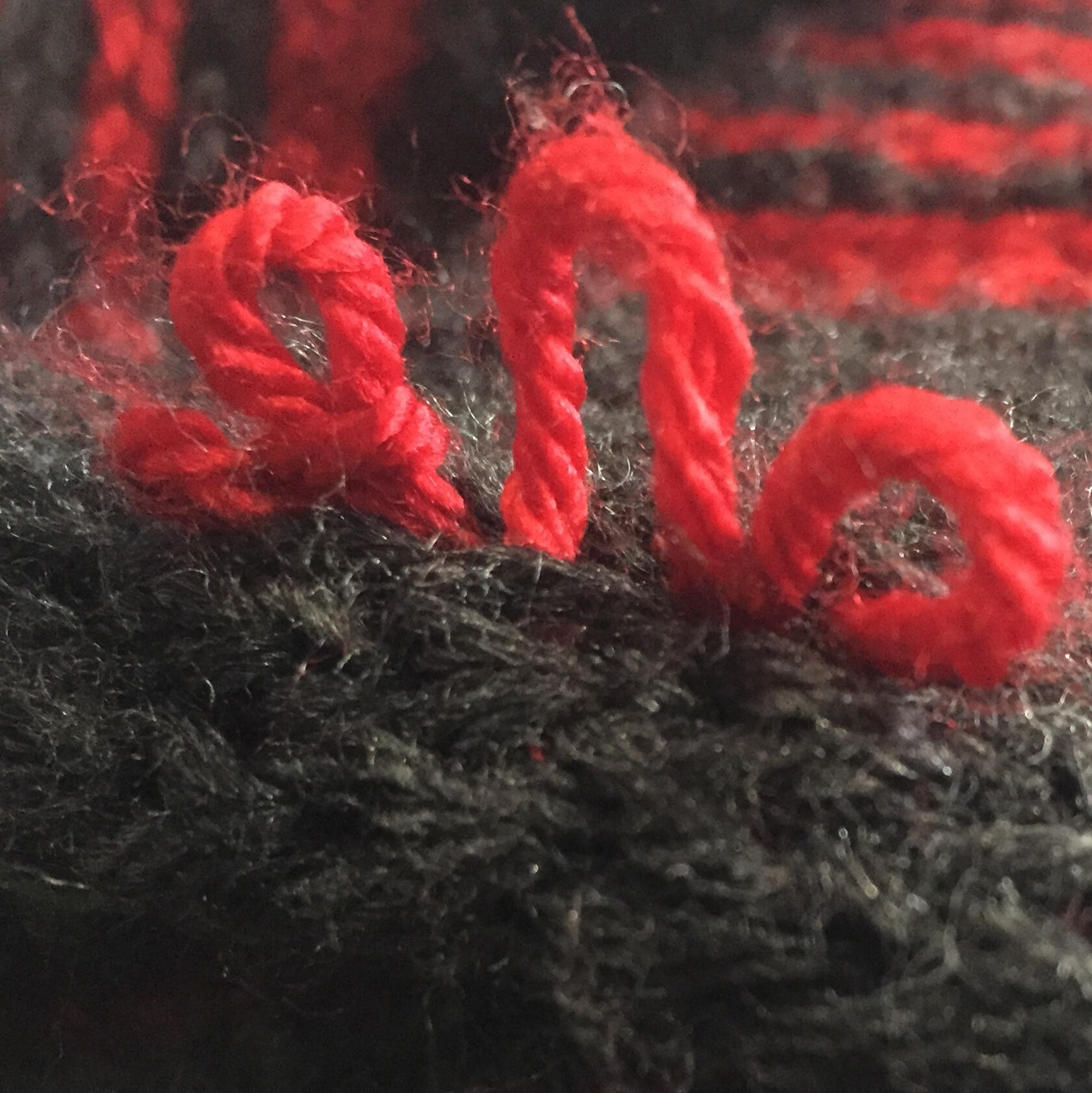

I developed knitting as an ethnographic modality for exploring how autistic people craft identities and communities that challenge clinical knowledge about autism. I approach knitting as a way to tell richer narratives about what it means to be autistic, including autistic experiencess of sensory differences, stimming, and special interests. Through my own special interest of knitting, I highlight disabled creativity and refute diagnostic language about autism as lacking. Knitting, either alone or with others, provides a nontextual way to document autistic life narratives and meaning-making, continuing histories of knitting as an act of protest and storytelling. You can learn more about this research on my project website: Crafting Autism

Knitting is conceptually and methodologically tied to my positionality as an autistic anthropologist. I am committed to knitting as a way to make autistic experiences quite literally material in the face of the continued erasure of autistic lives. I am also interested in how knitting as research method challenges ideas of what counts as meaningful, legitimate academic knowledge and who can create it.In addition to using knitting as a participatory research method, I also use knitting as a way to reflect on my own experiences as a disabled academic, as in my piece "Security Blanket: Neuroqueer Knitting in Pandemic Times" recently published in Lateral and "The Role of Spite in Keeping Your Warm" featured on Institutional Model.

Advocacy

Diagnosed as autistic shortly before starting college, my experiences of disability are deeply entwined with higher education. My anthropological training led to both curiosity and concern about how power structures limit access to education and professional development. Building from my own experiences of these shortcomings, I am passionate about anti-ableist practices in academia.In 2019, I participated in the Autistic Self Advocacy Network's Autism Campus Inclusion Program, where I solidified my commitment to make college more accessible to autistic and other disabled students. Since then, I have led multiple campus groups, coordinated events, lectured on disability policies, and advocated for change. I enjoy working with student groups, university leaders, and professional organizations on topics related to disability. I have helped make events more accessible and inclusive, as well as guest-lectured on a range of disability-related topics. I am a former board member for DREAM: Disability Rights, Education, Activism, and Mentoring.I have built my skills in legislative advocacy through trainings with the Indiana Statewide Independent Living Council and the National Association of Graduate and Professional Students. Though I believe that legislative advocacy alone is insufficient, I also recognize that policy has disproportionate impacts on disabled and other marginalized populations and work to reduce the harm caused by these structures.